Applying for a federal grant to support the creation of new charter schools is about to get a lot harder. That’s the upshot of draft regulations for the Charter Schools Program that the Biden administration released for public comment in March. It is an unfortunate proposal at a time when new research confirms that charter schools are an asset not only to their students but also to the broader communities in which they operate (see “The Bigger Picture of Charter School Results,” features, this issue).

For nearly three decades, Congress has provided funds to assist charter schools with start-up expenses such as staffing, professional development, facility improvements, and community engagement events. The bulk of the money goes first to state education departments who, in turn, award grants of up to $500,000 to charter schools preparing to open, replicate, or expand. When Congress last renewed the program in 2015, it permitted successful charter management organizations to apply directly to the U.S. Department of Education for comparable support.

The program is modest by federal budget standards—Congress authorized $440 million for it this year—but over time it has been a major driver of the charter sector’s expansion. What’s more, the states, none of which wants to leave federal money on the table, often design and implement their charter school programs according to the criteria Congress uses to select grant applicants.

That’s one reason the administration’s recent proposal is so troubling. Among other new requirements, the regulation would force applicants to submit a detailed “community impact analysis” demonstrating that the number of schools they propose to open or expand “does not exceed the number of public schools needed to accommodate the demand in the community.” The language says nothing about the quality of available schools. It would effectively prevent charter schools from opening with federal support in the growing number of areas with flat or declining enrollment—often places where high-quality options are scarcest.

The regulation would also require applicants to collaborate with a traditional public school or district on “an activity that would be beneficial to all partners in the collaboration”—a nice-sounding concept that would effectively give districts veto power over charter expansion. Applicants would even need to provide “a letter from each partnering traditional public school or school district demonstrating commitment to participate in the proposed charter-traditional collaboration.” Charter entrepreneurs unable to find a willing partner would be out of luck.

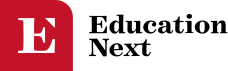

The entire proposal seems to reflect the view, heavily promoted by teachers unions and their political allies, that charter schools are a drain on school districts’ resources to be tolerated, if at all, as pockets of innovation within expanding systems. That same perspective has informed key revisions to state charter-school laws in recent years, including California’s 2019 move to allow districts to reject charter school applications based not on the proposal’s quality but on its impact on their finances. The result was a dramatic slowing of charter growth nationally in the years leading up to the pandemic—just as charter opponents intended.

Yet the research case for the charter sector’s expansion continues to strengthen. In this issue, Doug Harris and Feng Chen of Tulane University offer the most comprehensive analysis to date of how charter schools affect the combined outcomes of both charter and traditional public-school students in the school districts in which they are located. Looking nationwide and comparing districts with a substantial charter presence to those without charter schools, they find substantial gains in both test scores and high-school graduation rates. A January 2022 study by David Griffith for the Fordham Institute, “Still Rising: Charter School Enrollment and Student Achievement at the Metropolitan Level,” similarly found greater charter enrollment associated with increased math achievement by Black, Hispanic, and low-income students.

If Biden administration rule makers are not swayed by these findings, the reality underlying them is persuasive to many of the families who have chosen to enroll their children at charter schools. Despite an oddly short window for public comment, more than 25,800 members of the public, many of them charter parents, weighed in on the proposed rule before the April 18 deadline. A group of 17 Republican governors wrote to education secretary Miguel Cardona to register their objections to the proposed changes. When a similarly tone-deaf draft rule on civics-education grants prompted an uproar last year, the administration backed down and replaced the rule with something more sensible. Here’s hoping that pattern prevails again.

— Martin R. West

This article appeared in the Summer 2022 issue of Education Next. Suggested citation format:

West, M.R. (2022). New Biden Rules Would Slow Charter Growth: Parents, governors protest. Education Next, 22(3), 5.