The nation’s Covid-19 health emergency is over, but the K–12 education emergency remains. If we do not supersize our education recovery efforts, our nation’s schoolchildren, especially its most vulnerable, face a diminished future.

What researchers call “education’s long Covid” has three related culprits, beginning with student learning loss. “Different test. Same story,” is how Mark Schneider, director of the federal Institute for Education Sciences, describes the situation.

It is worsened by the other two culprits.

Student mental health has declined. By April 2022, 70 percent of public schools reported an increase in the percentage of children seeking school mental-health services compared to pre-pandemic levels.

And finally, chronic absenteeism—on average, missing at least 18 days of school a year—rose to an all-time high. In 2021–22, 25% of students were chronically absent, up from 15% before the pandemic.

If not reversed, economist Eric Hanushek calculates that the average student’s lifetime earnings will be 5.9% lower, leading to a GDP that is 1.9% lower for the rest of the century.

U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona calls the pace of efforts to deal with this crisis “appalling and unacceptable. It’s like . . . we’ve normalized [this situation].”

But there’s a potential way out. I propose five principles to guide a supersized K–12 post-pandemic recovery that builds on what states and communities are doing.

1. Promote student learning and teacher development

This “north star” guides the recovery effort. Its foundation lies in states and school districts using high-quality classroom instructional materials with aligned teacher professional development. Two examples are ripe for expansion. The first is led by the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO). It provides assistance to 13 states that have adopted high-quality, standards-aligned curricula linked with teacher professional development and then has those states working with their school districts to adapt the materials and professional development to local needs. The second is state-directed, legislative, bipartisan, and endorsed by one of the nation’s teachers unions, the American Federation of Teachers. It is inspired by Mississippi’s successful work to improve literacy based on the “new” science of reading. Tennessee’s early literacy initiative is an example of the success of this approach where 40% of third graders now read on grade level, the highest since Tennessee raised academic standards nearly a decade ago. States can implement similar approaches by consulting the resources produced by the CCSSO network’s community of practice, including its state implementation roadmap.

2. Provide students with extra support

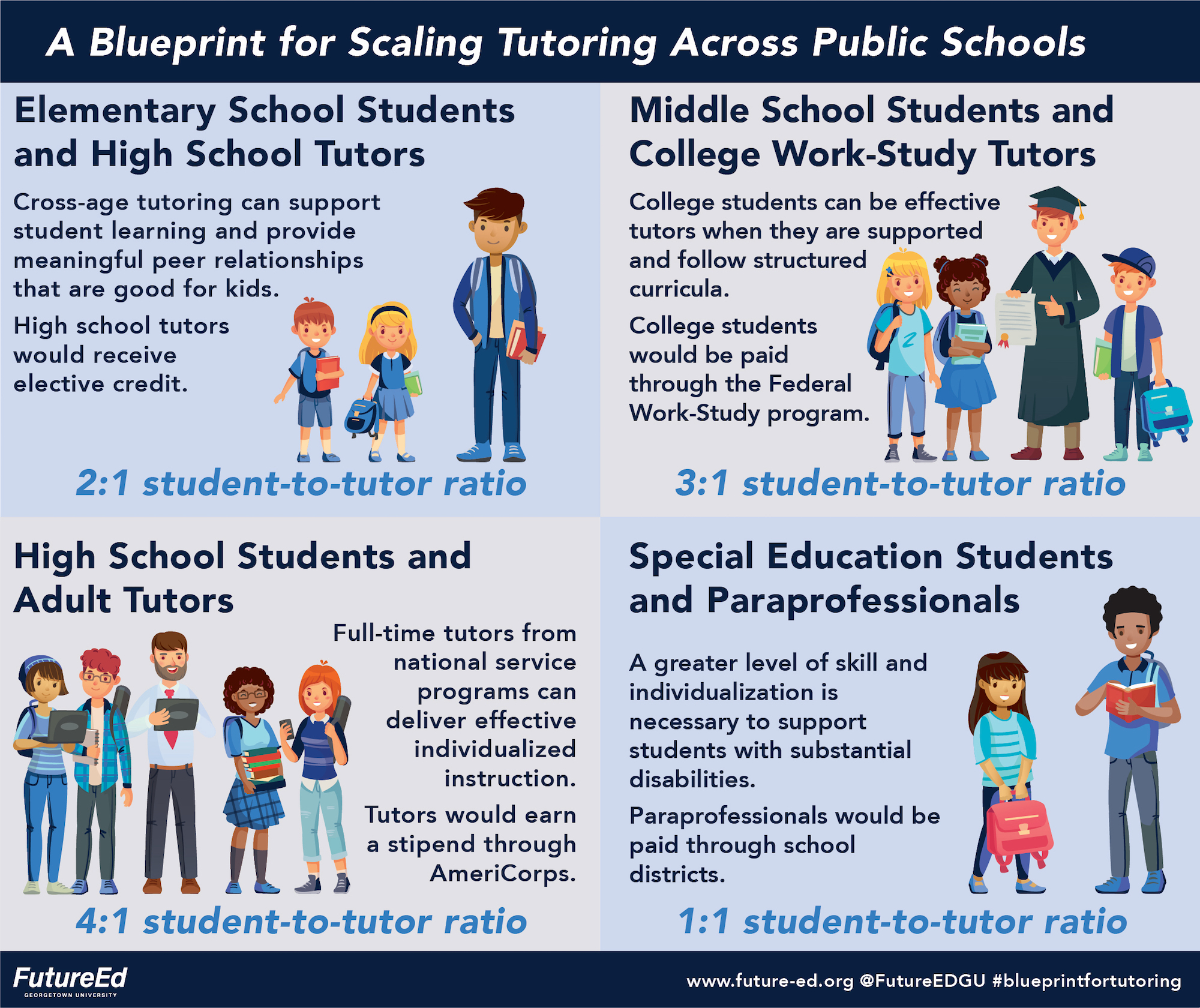

Some districts are using evidence-based programs that provide students with additional academic, social, and emotional support. Academic examples include intensive small-group and high dosage tutoring; competency-based instruction with students advancing based on what they know and do rather than by age; summer school; better use of student time on task; and offering financial incentives to students, parents, and teachers for reading books, attending classes, or—for teachers—achieving specific learning outcomes. Two studies on summer learning and tutoring programs provide a good lesson for supersizing these approaches: the key to implementation success is a school district program manager and support from principals, other school leaders, and parents. Additionally, schools need to provide students with “people-powered supports” that include mentors, tutors, and counselors. An example is the national effort led by the National Partnership for Student Success, a public-private partnership that has recruited an estimated 187,000 adults toward its goal of 250,000 by 2025. The Partnership has an easy-to-use online process for individuals, schools, districts, employers, colleges, and other community groups to get involved in this effort.

3. Give parents and children more options

School closures propelled parents to do two things. First, they discovered they could “unbundle” the all-in-one package of school services and separate them into separate services that meet particular student needs like extracurricular activities or tutoring. This led them to new, flexible learning arrangements like microschools, learning pods, and homeschooling. Second, parents chose new options for their children, including public charter and private and parochial schools. Policymakers have supercharged the ability of parents to pay for many of these options by creating new funding programs like education savings accounts that allowed families to pay for unbundled services and private school tuition. They also expanded other school-choice options like open enrollment across school district boundaries and tax-credit scholarships. This creates a more personalized and pluralistic K–12 system with educational options for families and kids.

4. Educate parents about the problem

There is a disconnect between the reality of pandemic learning loss and how well parents think their child is doing academically. Gallup reports that 3 out of 4 K–12 parents (76%) are “completely” or “somewhat satisfied” with the quality of education received by their oldest child, up from a 67% low in 2013 (contrast this with the American public at large where a record low of 36% are completely or somewhat satisfied). A Learning Heroes survey found around 9 of 10 parents believe their child is “at” or “above grade level” in math (89%) and reading (92%), with 8 in 10 (80%) saying they are confident they have a clear understanding of how their children are achieving academically. This disconnect between parents’ beliefs and the reality of learning loss is a barrier that K–12 stakeholders must overcome if young people are to recover from our education emergency. Learning Heroes has launched a muti-city campaign to get parents to ask teachers questions about how their child’s learning and what help them might need. Local leaders must undertake similar efforts.

5. Focus resources

States and districts still have at their disposal some of the federal $190 billion pandemic relief support, being spent at a “snail’s pace.” For example, the 25 largest school districts using remote learning for at least half the 2020–21 school year typically spent only about 15 percent of federal relief funds. Additionally, states continue to increase K–12 education spending, rising 8 percent in fiscal 2022. Finally, existing federal program dollars can be used for the recovery effort. The Tennessee literacy program mentioned above used federal Title I, Title II, and IDEA PART B to fund its work. Align these—and other resources—with the first four principles.

A Community Recovery Strategy

Based on this five point-agenda, here is a framework for developing a district plan for providing schools with the assistance they need to reverse learning loss and track their progress.

Communicate there is a problem. As mentioned above, parents generally do not realize the toll that learning loss has taken on students. That makes it vital that district and other community leaders communicate the severity and scope of the problem to parents and other stakeholders, ensuring they understand and acknowledge the pandemic’s harmful educational aftermath.

Develop a plan. The recovery plan must deal with at least a triad of issues: student learning loss, deteriorating student mental health, and increasing chronic absenteeism. It should describe how it will use high-quality classroom instructional materials and aligned teacher professional development and how students will receive academic, social, and emotional support. The plan would explain its use of initiatives, like high-intensity group tutoring, competency-based instruction, summer school, and people-powered supports like mentors and counselors. The idea is for all these efforts to build on the lessons learned from what has already been done.

Create a community report card. To ensure that the plan’s implementation remains on track and produces the desired outcomes, the community should establish a user-friendly Community Covid-Recovery Report Card. This would be a tracking system that reports progress on the various aspects of the plan, holding schools, local leaders, and other stakeholders accountable. The report card would provide a transparent look into how effectively strategies are being implemented, and which areas may need more attention or resources.

Focus community resources and action on the plan. A successful strategy needs financial, human, and other community resources to succeed. Aligning these resources with the recovery strategy and a unified community response will lay a strong foundation for student success.

Education’s long Covid will not go away by wishing it away. The burden is on K–12 advocates and stakeholders to up their game. This is an opportunity for genuine leadership, for rising to the challenge and mobilizing a recovery effort worthy of our students. If not, the consequence will be a Covid K–12 generation ill-equipped to pursue opportunity and reach their full potential.

Bruno V. Manno is senior advisor for the Walton Family Foundation program and a former Unites States Assistant Secretary of Education for Policy. Some of the organizations mentioned in this piece receive financial support from the Foundation.